Louis William Wain was born on the 5th of August 1860, under the astrological sign of Leo, in Clerkenwell, London, the eldest of six children born to William Wain, a textile trader and embroiderer, and his French wife Julie. His birth was followed by that of five sisters: Caroline in 1862, Josephine two years later, Claire in 1868, Felice early in 1871 and Marie just before Christmas of that same year. The family moved house quite often during Louis’ childhood, but always stayed in the Clerkenwell area of London.

Louis was born with a cleft lip and suffered from ill health so the family doctor gave his parents the orders that he should not be sent to school or taught until he was ten years old. By his own account, his early childhood was blighted by terrifying recurring dreams. He later wrote:

I seemed to live hundreds of years, and to see thousands of mental pictures of extraordinary complexity… But above all, I was haunted; in the streets, at home, by day and night, by a vast globe, which seemed to have endless surface, and I seemed to see myself climbing over and over it, until, from sheer fright I came to myself, and the vision went.

Eventually, after a bout of scarlet fever that Wain believed had ‘burned up all that was bad in my constitution’, the nightmares ended, and after a period of recovery, he was sent to school as his doctor had predicted at the age of ten. He first attended the Orchard Street Foundation School in Well Street, South Hackney. By the time he was 12, he had, he later recalled, ‘fought some heavy fights’ for his age, and his nose had been ‘flattened to his face.’

As a boy he developed a love for adventure stories set in far off locations and created fantasy worlds in his own imagination. He also developed an early ambition to become an artist as he was to tell journalist Roy Compton who interviewed him for The Idler in 1895:

My mother tells me that in my childhood I had always a great appreciation for colouring and used to amuse myself for hours grouping shaded leaves. I used to wander in the countryside studying nature and I consider that boyish fancy did much towards my future artistic life, for it taught me my powers of observation and to concentrate my mind on the details of nature which I should otherwise never have noticed.

He often played truant from school, preferring to visit museums or attend scientific lectures at the old Polytechnic Institute in Regent Street. On other days he would spend all day at the London docks watching the ships arriving from all parts of the world and listening to sailors’ yarns.

As someone so absorbed in the street life of the city, Louis couldn’t help but come into contact with the political orators who could be found on every street corner at that time. Their speeches aroused his sympathy or sometimes resentment at the injustices of the world and inspired him to read newspapers and take an interest in Parliamentary debates. This new-found interest in worldly affairs gave Louis a rationale to refocus his attention on his schooling and he soon became a more diligent student.

From 1876 onwards Louis attended St Joseph’s Academy in Kennington, where other pupils remembered him as an outsider who often seemed lost in his thoughts. He continued to truant whenever he felt like it, spending days wandering around London observing life in the busy streets. Looking back as an adult, he credited his inquisitive nature with helping to shape his future artistic life. He later wrote:

As a boy, my fancy trembled in the balance between music, painting, authorship and chemistry. I might in one sense say that I have had an art training, for I never contemplated being anything but an artist in one form or another.

Music became an all-encompassing passion for Louis at this time. ‘Contact with musical people determined me to devote my future career to music, and easy going masters carried me through a lot of work; and my circumstances allowed me scope to compose a great deal, including an opera made up entirely of choruses, quartettes and duets.’ He would continue to bring up the subject of his opera in press interviews later in life, even claiming at one time that he had submitted it to the famous conductor Henry Wood, though no trace of any musical composition has ever been found.

After leaving school, Louis studied for two years at the West London School of Art, staying on afterwards as an assistant teacher for another two years. This was partly out of necessity; his father had died in 1880, and he now had to support his mother and five sisters. He was not particularly successful as a teacher and didn’t enjoy the experience. His dream was to become an artist in his own right, so whenever he had the time he would work on sketches for his portfolio, which he hoped would set him on the path to success.

This ambition to become a professional artist eventually became so strong that in the summer of 1881 he left home and rented a furnished room. He began to collect around him ‘many hundreds of books, more or less of a scientific nature and a quantity of artistic properties.’

In the winter of that year he had his first success. ‘The first drawing I ever had published appeared in the Illustratrated Sporting and Dramatic News of 10 December 1881,’ he later wrote. ‘It was a picture of Bullfinches on the laurel bushes… and I did some 30 others, large drawings before I could persuade the editor to take another one, but persistency told.’ He was at this time still teaching at the West London School of Art but he was able to give up the position when Sir William Ingram, the editor of the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, gave him a job, sketching dog and agricultural shows.

Now that he felt more successful in his career, Louis decided to leave his rented room and return to live in the family home. Around the same time the Wain family hired a new governess, Emily Marie Richardson, to teach and care for the younger children. Although 10 years Emily’s junior, Louis fell in love with her, and she with him. For the rest of the family, however, it was a highly contentious relationship and the family strongly opposed their courtship. Undaunted, Louis and Emily left the household and moved into a new home together in Hampstead. On the 30th January 1884 they were married at St Mary’s Chapel, Holly Place, Hampstead. There were no members from either family present at the ceremony.

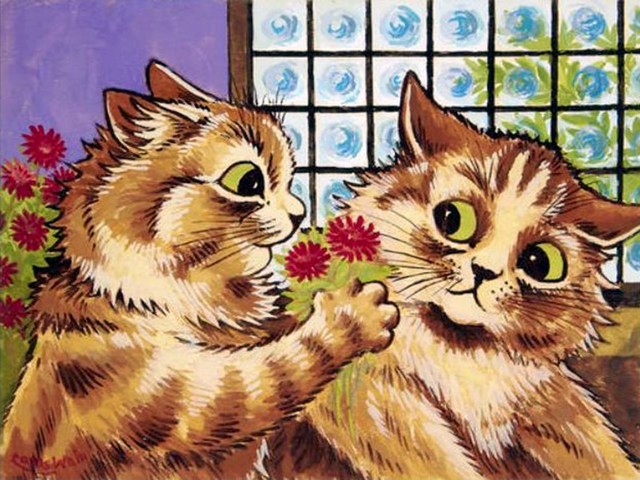

In the beginning the newly married couple were very happy. Sadly, though, soon after they moved into their new home, Emily Wain was diagnosed with breast cancer. She would spend much of the remaining three years of her life in bed. Their heartbreak was eased by the arrival in their household of a stray black and white kitten they had rescued after hearing him mewing in the rain one night. Emily’s spirits were greatly lifted by the cat who they called Peter. Louis began to draw sketches of him, which Emily encouraged him to have published. It was to prove a defining moment in the artist’s career as he recalled in his interview with Roy Compton:

I trained Peter like a child, and he become my principle model and the pioneer of my success. I suggested an idea to Sir William Ingram who had encouraged me greatly by taking some of my sketches, which showed promise but were not sufficiently good to reproduce. I worked upon the cat pictures until they finally caught his fancy.

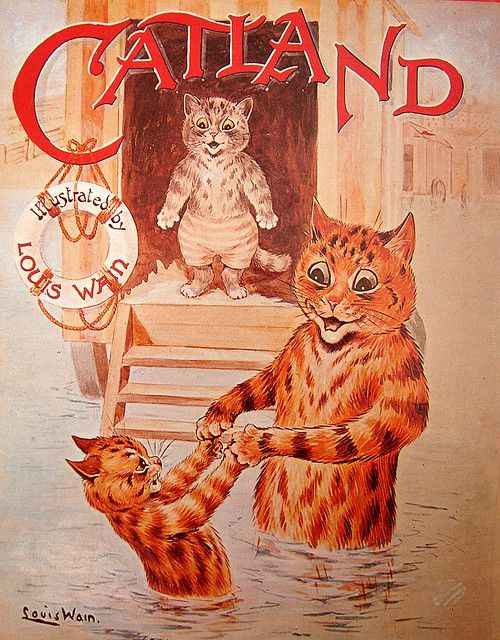

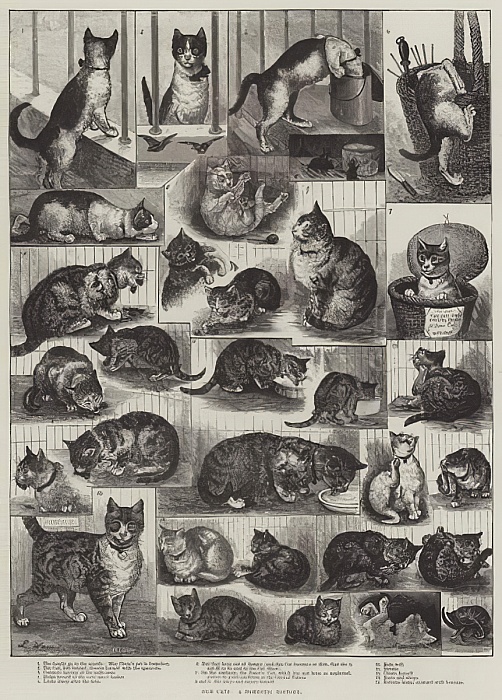

Wain’s first accepted cat picture did not, however, make its first appearance in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News but in Sir William Ingram’s companion weekly magazine, the Illustrated London News. The multi-paneled full-page illustration entitled Our Cats: A Domestic History that Wain contributed to the issue of 18 October 1884 is today acknowledged as a ground-breaking example of a narrative drawing featuring animals. The picture perfectly captures the domestic cat in all its moods, with Peter appearing in a number of the panels.

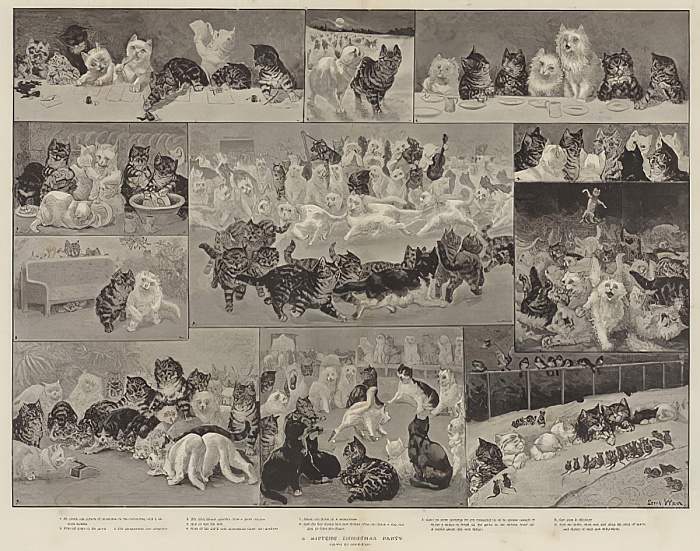

If one picture assured Louis Wain’s fame it was A Kitten’s Christmas Party, which Sir William Ingram commissioned for the Christmas 1886 issue of the Illustrated London News. The artist worked on the drawing as if his very life depended on it, drawing almost two hundred cats, sending invitations, holding a ball, playing games, and making speeches, spread over eleven panels. Still the cats remain, though, on all fours, unclothed, and without the variety of human-like expression that would characterize Wain’s later work. When A Kitten’s Christmas Party was published, the illustration created a sensation, and, in order that even more people might enjoy it, Sir William presented the original to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London for public display.

Tragically, only a week after this triumph, on 2nd January 1887, Emily Wain died. Despite the brevity of their marriage and his wife’s poor health, Wain was heartbroken, and to some people he was never the same man again. He grew shy and morose, and shortly afterwards moved to lodgings in New Cavendish Street. His only comfort was Peter who would live for almost another decade before dying peacefully in 1898.

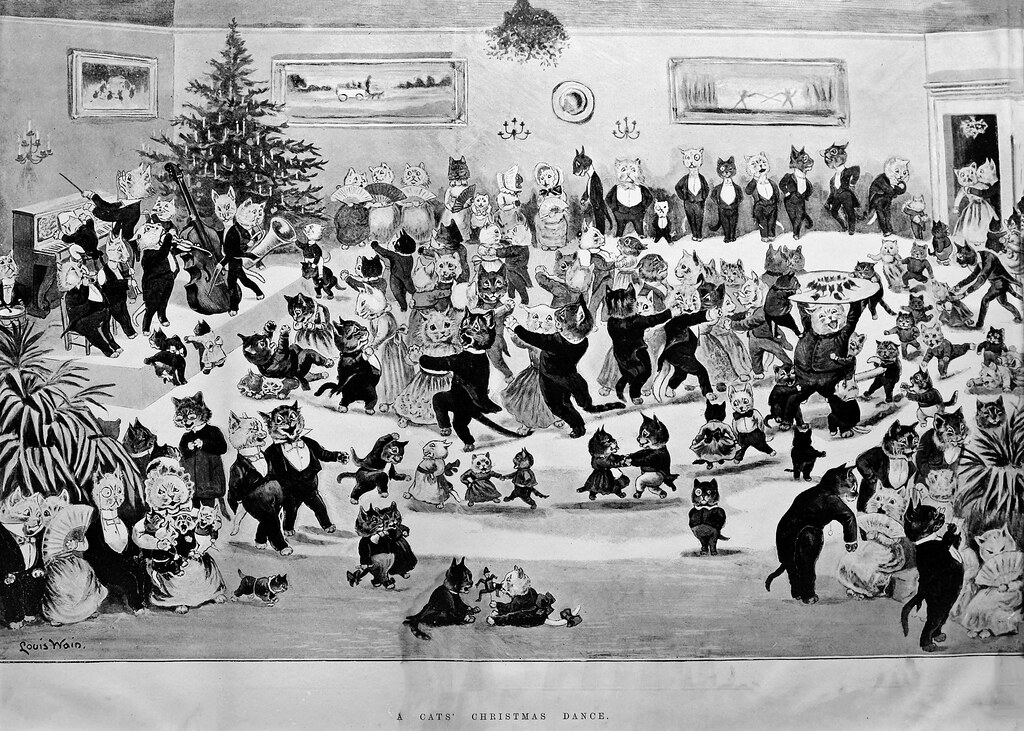

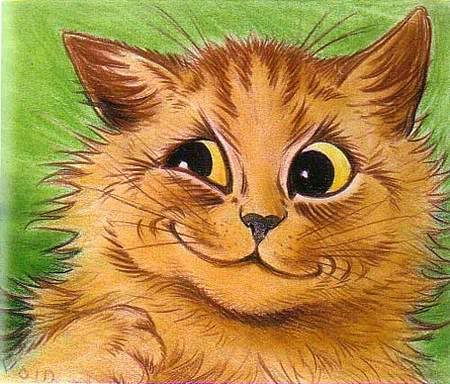

Although Louis continued producing drawings for Sir William Ingram’s Illustrated London News through 1888 and 1889, the anthropomorphized cats for which he became best known did not appear until the Christmas issue of 1890, when the Cats’ Christmas Dance and A Cat’s Party were published. In these two illustrations the cats are pictured wearing elegant evening dress, dancing on their hind legs, and playing musical instruments. The classic humanized ‘Louis Wain cat’ had been born at last.

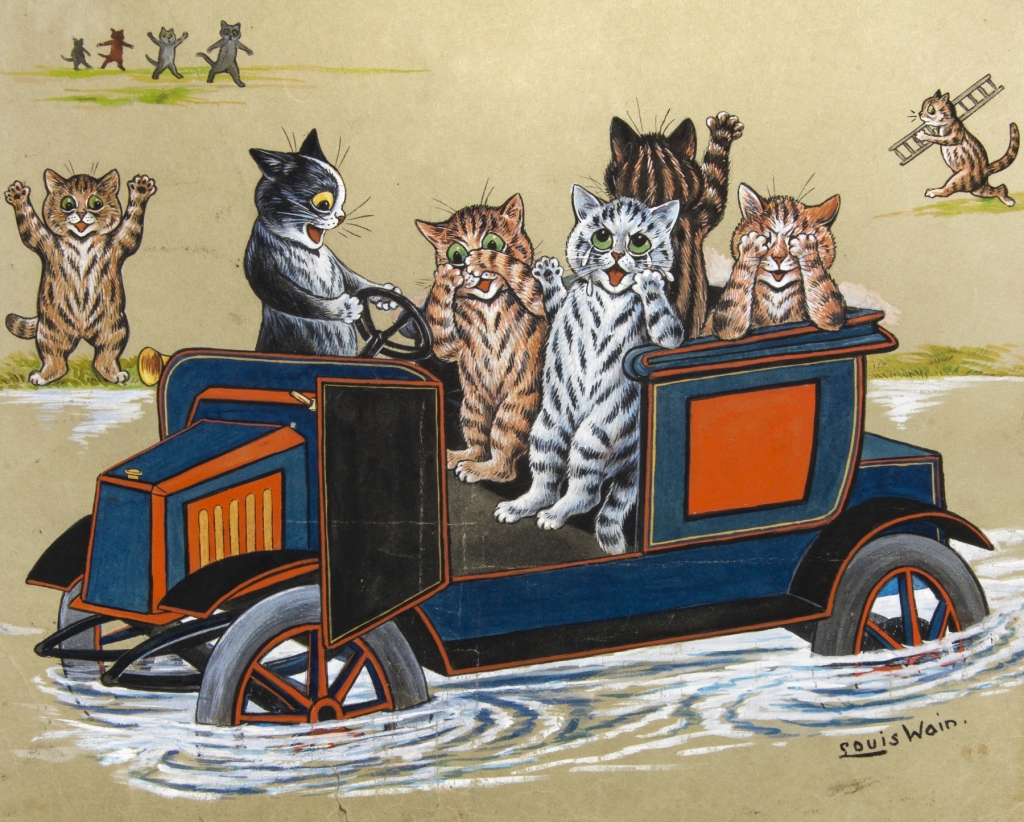

During the 1890s Wain worked for some of the most popular magazines of the time, including the English Illustrated Magazine, Windsor Magazine, Cassell’s, The Boy’s Own Paper and The Strand. His cats had begun to walk upright, smile broadly and use other human facial expressions. They wore sophisticated, contemporary clothing, played musical instruments, served each other tea, played cards, fished, smoked, and enjoyed a night at the opera. The British public loved them and Louis Wain had become a household name.

The artist later described one of the methods he used to capture the human characteristics be brought to his cat pictures:

There is another way of sketching cats, and this way I often resort to. I take a sketch-book to a restaurant or other public place, and draw the people in their different positions as cats, getting as near to their human characteristics as possible. This gives me double nature, and these studies I think my best humorous work.

Finally recognized as an artist in his own right, Louis became part of a social group that included some of the artists who had originally inspired him. Among them were illustrators for Punch and the Illustrated London News such as Harry Furniss, Alfred Praga, Phil May and Linley Sambourne. They would often meet socially in Fleet Street bars, or at Phil May’s Kensington studio, which was at that time a Mecca of all the artists and journalists of London. May’s satirical studies of day-to-day Victorian life were particularly influential for Wain. He adopted a similarly humorous style in his cat pictures, leading to his being dubbed ‘The Hogarth of Cat Life’ by Sir Frank Burnand, the editor of Punch.

As a mark of the fame he had now acquired, Louis was elected in 1890 to the Presidency of The National Cat Club. He devised the club’s coat of arms and its motto: ‘Beauty Lives by Kindness.’

At his first board meeting he declared that he would like ‘to bring all the different catty interests in harmony’. Breeding had by now begun to produce purer and stronger cats and a wider variety of breeds, and under his presidency the first known cat stud-book was a produced. In a later interview he commented on the positive effect the popularity of his cat drawings had had on public opinion:

I have tried to wipe out, once and for all, the contempt in which the cat has been held in the country and raised its status from the questionable care and attention of the old maid to a real and permanent place in the home. I have myself found, as the result of many years’ inquiry and study, that all people who keep cats, and are in the habit of nursing them, do not suffer from those petty little ailments which all flesh is heir to. Viz. nervous complaints of a minor sort. Hysteria and rheumatism, too, are unknown, and all lovers of ‘Pussy’ are of the sweetest temperament.

By now Louis’ mother and sisters, estranged since his marriage, had become aware of his growing fame and concluded that living a solitary life could not be good for him. Sir William Ingram brought about a reconciliation and suggested that they all settle in the town of Westgate-on-Sea, where he himself owned a number of properties. Reunited, the Wain’s moved to 16 Adrian Square, later moving in 1895 to 7 Collingwood Terrace.

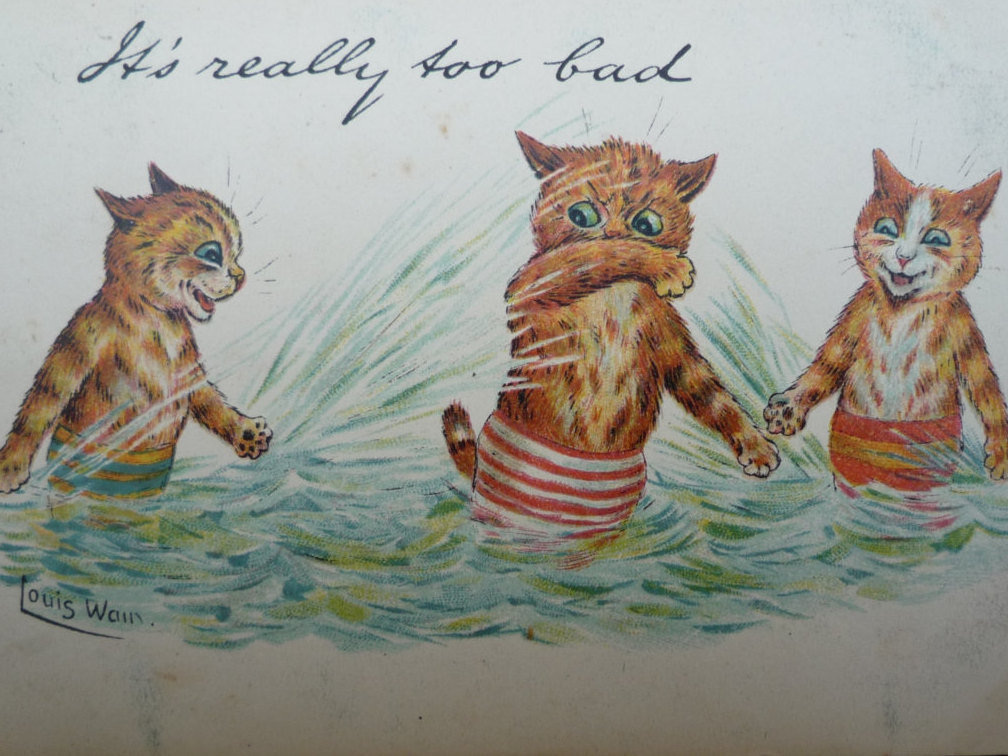

Having lived so long in London, the Wains were relieved to find themselves in a quiet seaside setting. Louis, now in his mid-thirties, found more opportunities for the kind of recreations he enjoyed like fishing, swimming, boating, fencing and boxing. His mother and sisters also enjoyed their new life at Westgate. Mrs Wain worked at embroidery and hangings for the church and Claire and Felicie painted and sketched. Despite their modest financial resources, they were happy.

The only black cloud hanging over the family was the behaviour of the youngest sister Marie who had begun to suffer from delusions. She believed she had leprosy and that her teeth were falling out. As a result she wouldn’t let anybody come near her. In 1900, at the age of 29, she was sent to a private mental hospital. A year later she was certified insane and admitted to a hospital near Canterbury (she died in 1913).

The Edwardian era saw Louis Wain reach the peak of his popularity. His cat pictures were now appearing, not only in magazines, newspapers and books, but also in advertisements and postcards. In 1901 the London publisher Anthony Treherne felt the artist’s popularity was such that he could publish a Louis Wain Annual. An editor was assigned to commission stories and poems, while Wain busied himself making a selection of seventy illustrations from his published work, as well as a number of new pieces. The annual was a huge success and further increased Wain’s fame. It continued to be published for many years and was an eagerly awaited Christmas present for thousands of children.

In 1902 Wain began another successful commercial collaboration with Raphael Tuck, who brought out a series of postcards by the artist that immediately found a ready market.

With all this fame and success Wain should, by now, have been a rich man, but like many artists he disliked having to bargain with editors for his work, often accepting far less for a picture than it was worth and failing to retain reproduction rights. Some took advantage by endlessly reprinting his illustrations without paying a penny in recompense. Inevitably, as commissions declined, in 1907 Wain fell into debt. Fortunately, just at this moment an invitation came from Hearst newspapers in America to cross the Atlantic and draw cats for its American readers.

On 12th October 1907, Wain sailed for New York where he was heralded by the press as ‘the world’s most famous cat artist’. His first cartoon strip for Hearst’s paper the New York American was a revival of Grimalkin – the ‘thin and lengthy of limb’ feline he had originally created for Girl’s Realm some years before. The popularity of the strip led to a second series, ‘Cats About Town’, which, like Grimalkin was syndicated across the country. Wain was surprised by the welcome he received in the country, which included invitations from the American Cat Fancy and their clubs across the country.

Wain’s original intention to stay in America for four months stretched to two years. Unfortunately, his luck ran out when he invested all the money he’d managed to save in an everlasting lamp that needed no oil. The apparently miraculous invention, however, never went into production and Louis lost the money he had speculated. His misfortune was compounded by news from home that his mother was gravely ill. He returned to England only to discover that she had died while he was at sea.

Broke, and seemingly out of fashion, Wain was in a worse financial state than when he left for America two years before. Nevertheless, he discovered there was still an audience for his work. Between 1910 and 1914, he produced illustrations for annuals and other books by Raphael Tuck, Routledge, Clark and other publishers. In 1914 he began designing what he called ‘futurist cats’ in china. These were produced by Max Emmanuel and Co, and nine individual designs were registered. Unluckily, two months after launching them, war was declared and a ship carrying a cargo of them to America was torpedoed, sinking all hope of a financial return on the project.

This, however, was not the worst of Wain’s misfortunes that year. On Wednesday 7th October 1914, he was boarding a London bus when he fell into the road, striking his head and being knocked unconscious. He was taken to St Bartholomew’s Hospital where he spent two weeks recovering. Journalists embroidered the incident by suggesting a cat was the cause of the mishap, reporting that, ‘the bus swerved and braked – to avoid a cat’. In later years, some even went so far as to attribute the start of Wain’s decline into madness to this accident.

In 1916, as the war raged across the channel, the Wains decided it would be safer to leave their home in Westgate and return to London. They packed up their belongings and moved in to a new house on Brondesbury Road in Kilburn. Louis found it harder than ever to pay the bills and was often forced to draw cat pictures for storekeepers and tradesmen instead of cash. He had some success with a series of war themed postcards featuring a soldier cat called ‘Tommy Catkins’ but this was short-lived.

Looking for other opportunities, Louis found work in advertising, drawing cat tea parties for Jacksons of Piccadilly.

He also illustrated posters, some of them for the cinema. These caught of the attention of the film pioneer H. F. Wood, who invited him to come to Shepperton Studios to try his hand at moving picture animation. Louis worked hard at the project but found the painstaking process of creating sixteen separate drawings for every second of film a strain.

The filmmaker George Pearson who befriended Louis when he was at Shepperton, recalled the artist’s unhappy experience in his autobiography:

I did my utmost to help his cartoon work, but the strange technique was difficult for him, although he strove with painful slowness to produce the animation which he knew was essential. Some three or four cartoons were completed but their cinema success was not great and in the end the venture was quietly abandoned.

Two years later, Felix the Cat, generally acknowledged to be the first animated movie star, made his first appearance. Felix would go on to star in over a hundred animated cartoons, becoming a world-wide phenomenon, raising the question of what might have been if Wain’s character had taken off.

In 1917, Louis’ eldest sister Caroline died, one of the many victims of the influenza epidemic then ravaging the world. Her death had a profound impact on Louis who had come to depend on her stability and strength of character.

Soon after the end of the war, the publishing firm Valentines commissioned Louis to illustrate a series of four books: The Tale of Little Priscilla Purr, The Tale of Naughty Kitty Cat, The Tale of Peter Pusskin and The Tale of the Tabby Twins.

Pleased with his work, the company then published Teddy Rocker, Pussy Rocker and Puppy Rocker. The illustrations in the book, when opened, stood up and rocked back and forth so that the eyes of the illustrated animals moved. Despite their novelty value, though, Louis’ name was not as much of a draw as it once had been and the books did not sell well.

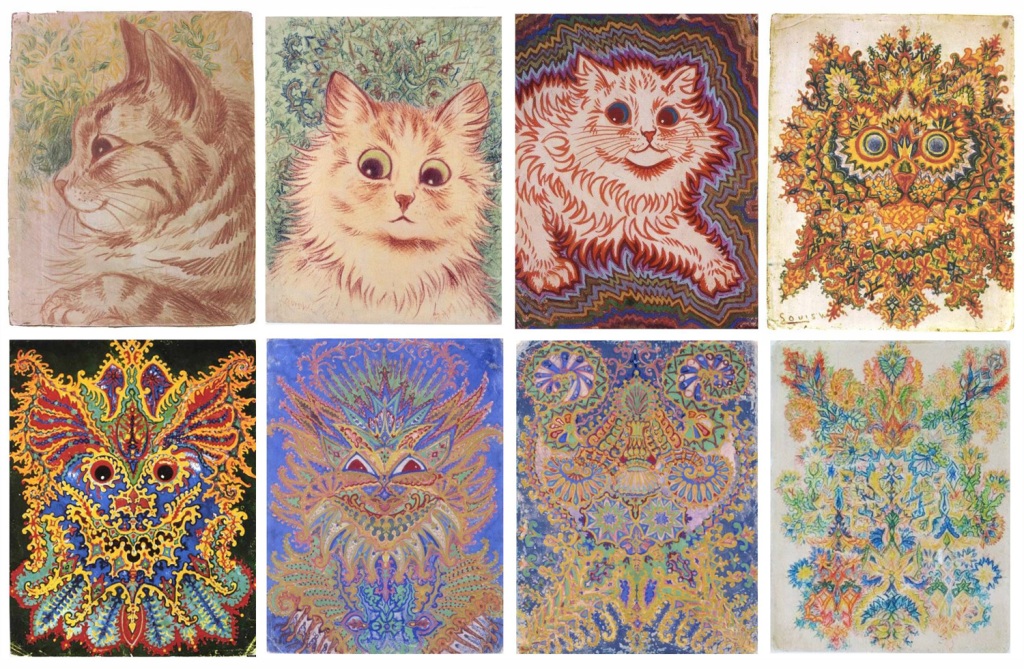

In 1921 Hutchinson published the last Louis Wain annual. One interesting aspect of many of the drawings was the inclusion of patterned fabrics such as curtains, chair-covers and carpets in the backgrounds. Although not the first time Wain had incorporated such details into his pictures, now the patterns were beginning to encroach on the foreground subject so that cat and background becoming indistinguishable. This abstract quality would become a recurring motif in many of Wain’s subsequent cat pictures, a manifestation, some have claimed, of the mental illness now affecting him.

Although known for being eccentric, it was becoming increasingly clear to Louis’ friends and colleagues that his mind was failing. He approached the noted cat fancier and editor of the publication Animals, H.C. Brooke, with a madcap idea to breed spotted cats. He also took to visiting leading members of the Cat Fancy claiming to be organizing the Crystal Palace Cat Show, a show that no longer existed. More seriously, he became paranoid that his remaining sisters – Claire, Josephine and Felice – were trying to steal from him, and spent more and more time locked away in his room writing long letters to acquaintances full of strange theories. Often he would emerge only at night when everyone else was asleep and move furniture around. Sometimes he would walk out on the street leaving the front door wide open. Most alarming of all, were the incidents of violence towards his sisters. On one occasion he grabbed Claire by the throat and pushed her out of the house. Another time he pushed his sister Josephine down the stairs when she tried to stop him moving a painting.

Finally, the situation became too much for the three sisters to handle. The doctors were called in, and on Monday 16 June 1924, Louis Wain was certified insane. He was removed to a pauper ward at Springfield Hospital, Tooting, the Middlesex County Mental Asylum.

At the hospital Wain told doctors he had been ‘bothered by spirits day and night for six years.’ The doctors diagnosed his condition as schizophrenia, and recommended he remain in the hospital. Yet despite his delusions, he settled down and soon started to draw and paint again.

Back at the family home in Kilburn the Wain sisters’ lives began to return to something approaching normality. They managed to make ends meet by giving sketching lessons, decorating glass and illustrating the covers of books. Every week they visited Louis at Springfield, bringing him crayons and sketch-books. At the end of their visits they took away any new art work he had produced.

Wain had been at Springfield Hospital for just over a year, when the hospital guardians made one of their periodic visits. One of them was Dan Rider, a well-known bookseller, who recalled noticing ‘a quiet little man drawing cats.’ ‘Good Lord, man’, exclaimed Rider, ‘you draw like Louis Wain.’ ‘I am Louis Wain,’ replied the patient, and Rider was astonished to discover he was.

Rider made contact with Mrs Cecil Chesterton, the sister-in-law of the writer G.K. Chesterton, and an appeal committee was set up. The Louis Wain Fund was launched at the beginning of August 1925. Some well-known donors to the fund included Lady Theresa Berwick, Princess Alexandra, and the author John Galsworthy. The Times wrote an article on the artist’s plight and the Chesterton appeal was printed in many papers in Britain, the United States and elsewhere. It described what Louis Wain had done for animal welfare and how he now came to be in a mental hospital. On 17 August 1925, The Daily Graphic launched a ‘Louis Wain Competition Week’ and published readers’ personal memories of the artist.

The following week the Prime Minister, Ramsey Macdonald, became personally involved. In his appeal he wrote: ‘Louis Wain was on all our walls fifteen to twenty years ago. Probably no artist has given a greater number of young people pleasure than he has.’ On Thursday 27 August, a message written by H.G. Wells was broadcast by the BBC. ‘Three generations,’ said Wells, ‘had been brought up on Wain’s cats, and few nurseries were without his pictures.’ He added: ‘He has made the cat his own. He invented a cat style, a cat society, a whole cat world. English cats that do not look and live like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves.’

As a result of the Prime Minister’s personal intervention, Louis Wain was transferred to the Royal Bethlem Hospital in St George’s Fields, Southwark. Louis had his own room in Bethlem and a place to keep his possessions. It was a more settled environment in which he could draw and paint whenever he felt in the mood. As at Springfield, he would often speak of his strange theories concerning health, science and politics but he was otherwise cooperative and friendly. It was here that he began experimenting with what some have called the ‘disintegrating’ cat – kaleidoscopic, two-dimensional pictures that some have claimed demonstrate the progression of the schizophrenic mind.

In 1930 the Royal Bethlem Hospital moved to new premises in Beckenham, South London, and it was decided that Louis Wain should be moved to the more rural environment of Napsbury Hospital, St Albans. In these idyllic surroundings of spacious landscaped gardens full of birds and animals he again worked sometimes with his easel or sketchpad. His drawings of this period often include idealized mock-Tudor buildings, based on the buildings in the hospital grounds.

The last exhibition of Louis Wain’s work was mounted at the Clarendon House Gallery in London in June 1937. Some 150 drawings were shown, priced from 10 shillings to £10. Amongst the newspapers reporting on the exhibition was the Daily Express who ran a story headlined – ‘Artist in Asylum Paints On.’

In November 1936 Wain suffered a stroke. By May 1939 he had become bedridden and unable to speak. He died on 4 July 1939 at the age of 78, and was buried in plot 3654 in St Mary’s Cemetery, Kensal Green, alongside his father and his sisters Caroline and Josephine (the two other Wain sisters also died not long afterwards – Felice in 1940, and Claire in 1945).

Louis Wain’s gentle genius was quickly forgotten as Britain became embroiled in the Second World War. It would be nearly thirty years before a first biography in 1968, and an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1972, helped spark a revival of interest in his work. Since then there have been a number of further biographies, numerous articles, and regular exhibitions of his artwork. Sales of his prints and postcards have increased and books containing his illustrations now sell for several hundred pounds. A feature film about his life starring Benedict Cumberbatch is due to be released in 2020.

Louis Wain was one of the best-known popular artists of his time. It is estimated that he drew over 150,000 pictures of cats during his career, although the true number will never be known. Through his art he gave a great deal of pleasure to a great many people. Not only that, he also used his talent and fame for good causes, in particular helping to improve the status of the cat and promoting animal welfare generally. Despite this, in his personal life, he was often unhappy. Tragedy and disappointment seemed to follow him through his life, often as a result of his inability to come to terms with reality. And, as we have seen, he spent the later years of his life confined in what, at the time, were referred to as insane asylums. Yet, even here, he continued to create art. We will never know exactly what it was that caused Louis Wain’s mental affliction, but what cannot be disputed is the enduring appeal of Louis Wain’s cats, who continue to delight and entertain to this day.

I really enjoyed reading about Wain. Excellent stuff. Thank you for all your research

LikeLike

Thanks for getting in touch. I’m glad you found it interesting.

LikeLike

Thanks for the information about Louis Wain. He seemed like a wonderful person and extremely talented. Unfortunately, he lived in a time when no one knew what his problem really meant. His will to go on is admirable. The movie was wonderful, too. Prime TV has picked a winner.

LikeLike

Thank you for your comment. I’m glad you enjoyed reading the article. I’m looking forward to seeing the film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this. Enjoyed the detail, the photos, and the illustrations. Just watched the movie.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your comment. It’s great to know Wain’s amazing pictures are getting the recognition they deserve.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on TheAchilles Butterfly and commented:

What a stunningly beautiful write-up about this magnificent man.

As a poet, I have had my poem “Cat as Radiant being” published recently, and in it I say “all I am Is Cats- that is my motto-

I think, without realizing it I have meant it as a tribute to him-

I saw the film last night and was transfixed. I suppose that was the way it was meant to be.

This man will live in our hearts and minds and on our walls forever. And as long as cats are- they will have him to thank for it. Just as we do-

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for your kind words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for this detailed biography of Mr Waine. What a nice person! I learned of him through the film (Cumberbatch is marvellous in it!) and I must say that your article is the best I’ve read so far! Thank you again!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for your feedback. I’m glad you enjoyed the article.

LikeLike

The film about Louis Wain led me to your article. Thank you for writing about this wonderful artist…and his creative if tragic life. But he did have Emily & Peter…and we have him and his art!,

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I’m glad you enjoyed the biography. I’m looking forward to seeing the film.

LikeLike

VERY good article. It was just what I was looking for in terms of more detail on Wain’s life. You seem to have an appreciation for the fellow and a kindness about your telling of him. That means a great deal. Thank you for your considered efforts! Have a wonderful Christmas and a Happy New Year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks for your kind comments. I’m glad you found the biography informative. A Happy Christmas and New Year to you.

LikeLike

This was really interesting, thank you. Can I ask a detail question? I can’t find a Collingwood Terrace.in Westgate, can you tell me where you found out about this address? A site is selling a picture of his house in Westgate here

https://www.mediastorehouse.co.uk/mary-evans-prints-online/new-images-august-2021/louis-wains-house-westgate-on-sea-kent-23271874.html

and that definitely isn’t in Adrian Square, but I have no idea where Collingwood Terrace is. Perhaps it now longer exists

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your comment. I researched Wain’s life some years ago now and read a number of different books and other sources, but I’m afraid I didn’t keep a record so I don’t remember where I came across that detail. I have visited Westgate but was unable to find Collingwood Terrace, although I did find Collingwood Close in the middle of a more modern housing estate, so I wonder if the Wain family house was knocked down to make way for this development.

LikeLike

Wain lived at 7 Collingwood Terrace and later at 10 Collingwood Terrace, both of which he named Bendigo, after a well-known prizefighter. That street has been renamed Westgate Bay Avenue, and the house numbers are 23 and 29. Source: https://www.margatecivicsociety.org.uk/Margate%20Civic%20Society%20-%20Spring%20Newsletter%20(358).pdf

LikeLike

Thanks very much for that information. I look forward to visiting the street and seeing the houses next time I’m in Westgate.

LikeLike

Thank you for this informative and insightful look into the life of Louis Wain. It has inspired me to seek out his work to display in my home.

LikeLike

I loved your article! I stumbled upon it in my quest to learn where Emily was buried? Do you happen to know?

Thank you very much.

Kathrine

LikeLike

Thank you very much for your kind comments. I looked back through my notes and I’m sorry to say I could not find any information about this. Since Louis and Emily lived in Hampstead, I would guess she was buried in one of the cemeteries there. Best of luck finding out anything more.

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just watched “The Electric Life of Louis Wain” on Prime Video. It is an excellent movie and I appreciate the additional information about his life. Of course Benedict Cumberbatch is an actor, but what struck me about his performance of Louis Wain was the energy and internal imagination he has. It makes me think Mr. Wain could possibly have had Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and possibly be on the Autistic Spectrum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your wonderful article, which has added to my appreciation of the movie. I’m curious, what did you think of The Electrical Life of Louis Wain?

LikeLike

Thank you for your kind comment – I’m glad you enjoyed the biography. I had some reservations about the movie, but I thought the performances were good, and I’m glad it’s increased awareness of Wain’s amazing art.

LikeLike